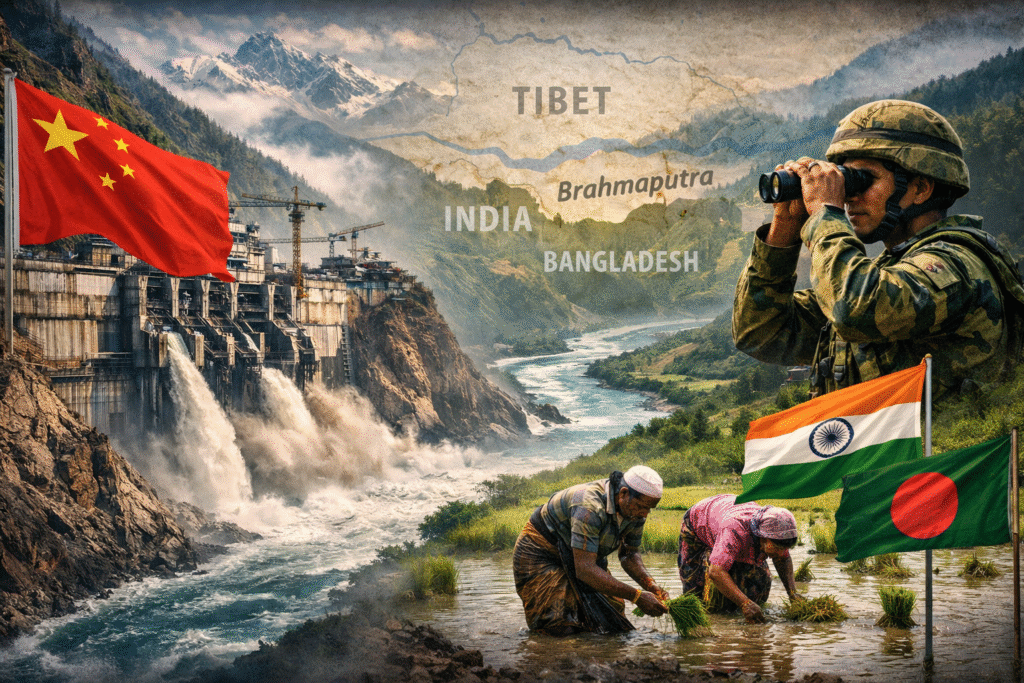

In the high, wind-swept plateaus of Tibet, a river begins its long journey toward the plains of South Asia. Known as the Yarlung Tsangpo in its upper reaches, this mighty watercourse becomes the Brahmaputra as it enters India—then flows into Bangladesh, where it nourishes fertile floodplains and sustains millions of lives.

Now, near the rugged border with India’s northeastern state of Arunachal Pradesh, China has embarked on constructing what might become the world’s largest hydropower dam, a project that promises vast electricity generation, development for remote regions, and a landmark achievement in engineering.

But beneath the ribbon of concrete and cables lurk concerns that stretch far beyond Tibet’s scenic gorges—raising alarms in New Delhi and Dhaka about rivers, rights, and regional power dynamics.

Rising Waters, Rising Stakes

At the heart of this unfolding story is the Medog Hydropower Project, also known as the Yarlung Zangbo/Brahmaputra dam. Approved by Beijing and now under construction along the river before it crosses into India, this project is massive in scale and ambition.

Once completed, it is expected to generate significantly more power than the Three Gorges Dam—currently the world’s largest hydroelectric facility—and could supply electricity to millions of households while advancing China’s renewable energy goals. Business Today+1

Chinese officials maintain the project is an exercise in clean energy and disaster prevention, and have repeatedly insisted that it will not harm water flows to downstream neighbours. They point to consultations and hydrological data sharing as evidence of cooperative intent. The Economic Times

But that assurance has done little to calm anxieties in India and Bangladesh, where many see the dam not merely as infrastructure—but as a potential geopolitical lever in a region already fraught with rivalries and distrust. The Indian Express

Water and Power: A Strategic Confluence

Water is more than a natural resource in South Asia; it is a cornerstone of agriculture, industry, transport, and culture. The Brahmaputra alone supports tens of millions of people with irrigation, fisheries, and drinking water across India and Bangladesh. Interruptions to its flow could ripple through entire economies, exacerbating droughts, flooding, and food insecurity. The Indian Express

India’s Concerns

For India, the stakes are high on multiple fronts:

- Hydrological Control: As the upper riparian state, China holds strategic control over a river that millions of Indians depend on. Seasonal management of water—how much is released or withheld—can influence agricultural cycles, hydroelectric reservoirs, and flood mitigation downstream. BISI

- Weaponization Fears: Indian officials and analysts have warned that in a crisis, water infrastructure could become a form of leverage. The idea of a “water bomb”—a sudden release of water to cause flooding—has entered public discourse, though such an action remains speculative. The Economic Times

- Seismic and Ecological Risks: The Himalayas are one of the most seismically active regions on Earth. Building enormous dams in such terrain raises the spectre of landslides, earthquakes, and dam failures that could unleash catastrophic floods in Assam and beyond. Drishti IAS

- Diplomatic Gaps: China is not a signatory to major international water treaties like the UN Watercourses Convention, meaning there is no binding framework for equitable sharing or dispute resolution over the Brahmaputra. Foreign Policy

This constellation of fears has pushed India to monitor the project closely and even accelerate its own hydropower plans on the Siang River—a major Brahmaputra tributary inside Indian territory—to bolster buffer capacity and maintain control over water resources. Al Jazeera

Bangladesh: A Delta in the Balance

If India watches the dam with unease, Bangladesh watches with existential urgency.

The Brahmaputra joins the Ganges to form one of the world’s most fertile delta systems, underpinning the nation’s agrarian economy and providing water for over half of Bangladesh’s irrigation needs. A small reduction in flow—just a few percentage points—could translate into significant drops in agricultural output, increased salinity intrusion along the coast, and heightened vulnerability to storms and sea-level rise. The Indian Express

Riverine sediment, carried downstream over centuries, enriches soils and shapes floodplains. Dams that trap sediment can starve land of nutrients, harm fisheries, and alter the delicate balance of river channels—changes that would be deeply felt across Bangladesh. Reddit

Bangladesh’s leadership has called for greater transparency and data sharing from China, but without binding agreements, much depends on diplomatic goodwill in an otherwise competitive regional landscape. Business Today

Ecology and Local Life: Beyond Borders

Downstream water security is only part of the equation. The dam site sits in one of the world’s richest biodiversity hotspots, home to endemic species and fragile ecosystems. Large dams can alter water temperatures, block fish migrations, and encroach on land—impacting flora and fauna that have adapted to the Brahmaputra’s rhythms for millennia. Wikipedia

Meanwhile, Tibetan communities themselves could face displacement and landscape change akin to what happened with China’s Three Gorges Dam, which relocated over a million people. Local voices—often obscured in geopolitical debates—remind us of the human cost of megaprojects built far from urban centers. Drishti IAS

The Geopolitical Undercurrent

The backdrop to this water narrative is a wider story of China’s assertive regional posture and India’s strategic anxieties.

China’s infrastructure push in Tibet, including transportation corridors and new administrative regions, is seen in some Indian strategic circles as a way of cementing control over border areas. Water infrastructure, in this context, becomes both a resource and a symbol of influence. The Economic Times

For India, managing relations with Beijing involves a careful blend of vigilance and diplomacy. Mechanisms like the Expert Level Mechanism (ELM) exist to share hydrological data during flood seasons, but these arrangements have been patchy and sometimes suspended during political tensions. Business Today

Bangladesh finds itself balancing relations with both India and China—each a major economic partner—while trying to safeguard its water and food security. This delicate balancing act underscores how transboundary rivers can entangle regional players in webs of interdependence and rivalry alike.

Looking Ahead: Conflict or Cooperation?

Water scarcity and climate change are already stressing South Asia’s environmental and social fabric. Monsoons are becoming more volatile, glaciers are melting faster, and demand for water and energy continues to rise. Big dams like China’s Tibet project are meant to address some of these pressures—but they also raise new questions about shared stewardship of natural resources.

Experts argue that more transparent, legally binding mechanisms for transboundary water management are needed to prevent disputes and promote sustainable use. Without them, rivers like the Brahmaputra could become flashpoints in broader geopolitical rivalries—a scenario no nation wants, especially when millions of livelihoods are at stake.

As the concrete rises beside the Yarlung Tsangpo, the world watches to see whether this project will be a symbol of mutual benefit or a catalyst for long-term tensions. For the millions who depend on the Brahmaputra’s waters from the Tibetan plateau to the Bengal delta, the outcome will shape their lives for generations.