When Niger, Burkina Faso, and Mali announced their withdrawal from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), many observers initially treated it as another chapter in the region’s long-running tension between military regimes and civilian-led regional institutions. But what has followed suggests something more ambitious—and potentially more destabilizing.

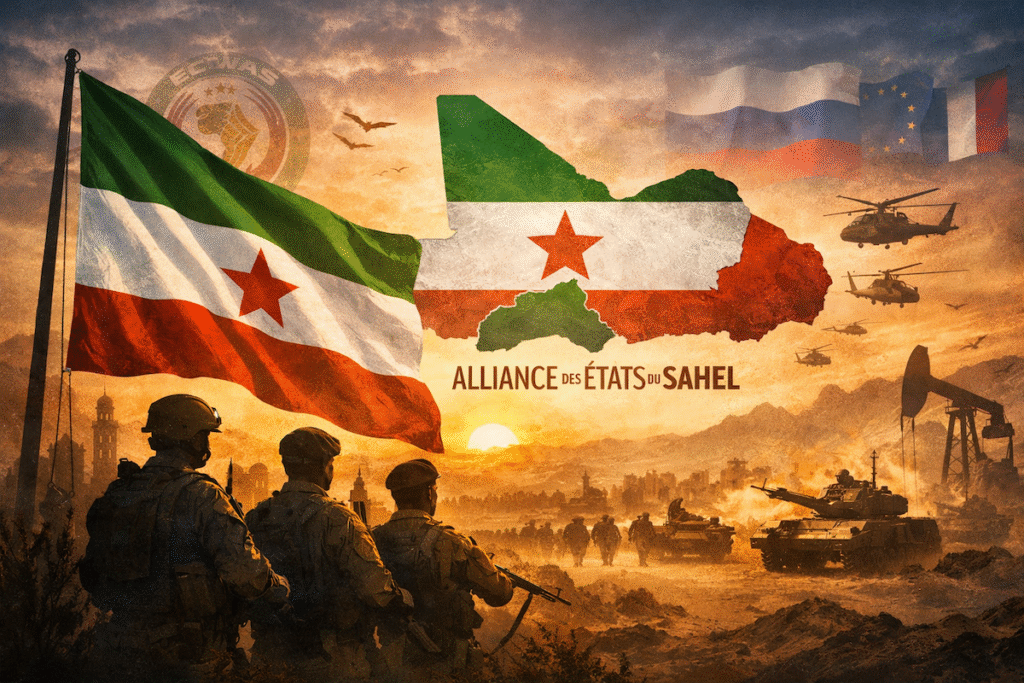

The three landlocked Sahelian states are no longer merely defiant members on the margins of a West African bloc. They are actively constructing an alternative political project: the Alliance of Sahel States (Alliance des États du Sahel, or AES). And behind the rhetoric of sovereignty and security lies a provocative idea that until recently would have sounded implausible—that a new country, or at least a quasi-state confederation, could emerge from this alliance.

The Break with ECOWAS: More Than a Diplomatic Snub

ECOWAS has long positioned itself as one of Africa’s most assertive regional organizations, particularly on questions of democratic governance. Its swift sanctions against military juntas in Mali (2020, 2021), Burkina Faso (2022), and Niger (2023) followed a familiar playbook: suspend membership, impose economic penalties, and demand a rapid return to civilian rule.

But this time, the pressure backfired.

Rather than isolating the juntas into submission, sanctions deepened their sense of shared grievance. Leaders in Bamako, Ouagadougou, and Niamey framed ECOWAS not as a neutral arbiter, but as an instrument of external powers—particularly France and, by extension, the West. The bloc’s threat of military intervention in Niger after the July 2023 coup proved to be a decisive turning point.

By early 2024, the three countries formally withdrew from ECOWAS. It was an unprecedented move in the organization’s nearly 50-year history—and one that signaled a rupture not just institutional, but ideological.

Enter the Alliance of Sahel States (AES)

Initially launched as a mutual defense pact, the AES quickly evolved into something broader. Official statements now emphasize:

- Collective security, with an attack on one treated as an attack on all

- Policy coordination across diplomacy, defense, and economic planning

- Rejection of external “interference”, especially from Western governments and institutions

What began as a security alliance increasingly resembles the scaffolding of a political union.

Joint military commands are being discussed. Cross-border operations against jihadist groups are already underway. Leaders speak openly about harmonizing foreign policy positions, currencies, and even travel regimes. Symbolically, the alliance presents itself as the true heir to Sahelian sovereignty—untethered from post-colonial arrangements and Western conditionality.

In effect, AES is not merely exiting ECOWAS. It is attempting to replace it—at least in the Sahel.

The Logic of a New State

Talk of a “new country” emerging from AES is still speculative, but it is no longer fringe speculation.

Confederations often begin as practical responses to shared threats. Over time, necessity can harden into identity. The Sahelian juntas already share strikingly similar narratives:

- Democracy, they argue, failed to deliver security.

- Borders inherited from colonialism are ill-suited to fighting transnational insurgencies.

- National sovereignty must be reclaimed from foreign influence—political, military, and economic.

From this perspective, a confederated Sahelian state—or a deeply integrated union with shared institutions—could be presented not as fragmentation, but as decolonization completed.

There is historical precedent. The short-lived Mali Federation of the late 1950s attempted something similar, uniting Senegal and French Sudan (modern Mali). Elsewhere, the United Arab Emirates began as a loose confederation of sheikhdoms before becoming a recognized state. Even the European Union, often cited as the opposite model, started with coal and steel cooperation before evolving into a quasi-political union.

The difference is that AES is being built under military rule, amid war, and in direct opposition to a powerful regional bloc.

Security as the Glue—and the Gamble

The strongest argument for AES integration is security. The Sahel is the epicenter of one of the world’s fastest-growing jihadist insurgencies. Groups affiliated with al-Qaeda and Islamic State operate seamlessly across borders, exploiting weak states and vast ungoverned spaces.

For the AES leaders, national borders have become liabilities. Coordinated command structures, shared intelligence, and unified military doctrine promise efficiency that individual states have failed to achieve.

Yet security is also the alliance’s greatest gamble.

Despite years of expanded military rule, violence has not significantly declined. Civilian casualties continue to mount. If AES cannot demonstrate tangible improvements—territorial control, reduced attacks, restored basic services—the legitimacy of a deeper political union will be fragile.

A new state born out of insecurity risks being defined by it.

Russia, the West, and a Multipolar Sahel

No analysis of AES can ignore geopolitics. As relations with France and the United States deteriorated, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger pivoted decisively toward Russia. Wagner-affiliated forces (now reorganized under different banners) have replaced French troops, while Moscow offers diplomatic cover and military support without democratic conditions.

AES thus fits neatly into a broader global pattern: regional defiance in a multipolar world.

For Russia, a unified Sahelian bloc hostile to Western influence is strategically valuable. For China, stability—regardless of regime type—matters more than governance norms. For the West, AES represents a worrying precedent: a regional order openly rejecting liberal democratic enforcement mechanisms.

If AES were to formalize into a new political entity, recognition would likely be uneven. Some states might quietly engage. Others would refuse outright. The result could be a gray-zone polity—functionally real, diplomatically contested.

What This Means for Africa

The emergence of AES challenges a core assumption of post-Cold War African politics: that regional integration would move steadily toward larger, rules-based blocs. Instead, West Africa now faces fragmentation along ideological lines—between sovereignty-first military regimes and democracy-enforcing institutions.

If a new Sahelian state or confederation emerges, it could inspire imitation elsewhere. Regions dissatisfied with existing blocs may decide exit is preferable to reform. The African Union, already cautious, may find itself navigating a continent of parallel regional orders.

A Country in the Making—or a Moment of Defiance?

Whether AES becomes a new country, a durable confederation, or a temporary alliance of convenience remains uncertain. What is clear is that Niger, Burkina Faso, and Mali are no longer acting as isolated military regimes. They are articulating an alternative vision of statehood—one rooted in security, sovereignty, and resistance to external pressure.

In the Sahel, borders drawn in European capitals a century ago are being questioned not by separatists, but by states themselves.

And that may be the most radical development of all.